CHAPTER I

Print Is Dead

Modern literature rarely moves me.

Most of it just limps past like an out of shape runner competing in a major event. Out of breath, panting, lacking the common sense to just give up already, go home, get in shape, and try again next year. Or best yet, never.

Modern bookstores are unbearably depressing. Like visiting a sick relative in a hospital—the one you don’t even like, but must, because family gets twitchy about such things. In the aisles, hundreds of lifeless books lie propped in neat little beds—sick, hopeless, terminal cases on life support—staring at you with blank eyes, begging you’d stop for a visit. You don’t know whether to flip through their pages or leave a bouquet, a sympathy card, and maybe even a bedpan. Or, if you’re lucky and no one’s looking, snuff them with a pillow and end their misery.

A decade ago, they gave us Fifty Shades of Grey — a book that proved two things:

a) We’re unmistakably in the final act of the sixth mass extinction — y’know, species collapsing, oceans acidifying, forests gasping for breath, and humanoids reverting to single-celled reasoning capacity of algae.

b) Anyone with a laptop and a repressed fantasy can end up on Time’s “100 Most Influential People.” And rub elbows with the likes of Hillary Clinton, Benjamin Netanyahu, Rihanna, and Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy. Bah. More like End of Times: guest-list for the planet’s most boring afterparty.

Fifty Shades of Grey is like those weird, obscure films they have playing in buses you don’t remember getting on. The kind you end up watching anyway, because you’re bored of watching passing clouds and fat, lazy cows — and the unusually shiny bald spot of the passenger in front.

Then came The Girl on the Train — disguised as a psychological thriller, when in fact it’s a fable. A heartwarming bedtime story for adults that warns them.. what exactly happens when you don’t try.

Damnit, you end up churning a New York Times best-seller. BY THE BEARD OF A BEWILDERED BABOON?! That it sold twenty million copies is the real murder mystery here— the cold-blooded murder of the intelligence of the world, executed with exact precision, and the killer gets away first class.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

if you really want some psychological thrills on a train, I suggest to get the sandwiches served on the Islamabad Express. Those greasy nasties have been decomposing on the counter since the Zia era. And things happen to mayo in the sun, man — strange, microbial, unexplained things. That’ll get your insides stirring faster than Paula Hawkins can spell diarrhea.

And how could one truly forget (or forgive) The Alchemist? A young man’s quest for self-discovery, set in a land that’s supposed to be the Sahara. They call it a desert, and yet I remain suspicious. The sand never quite bites, the sun never quite burns. Perhaps Coelho’s desert is a throwback to the Sahara of twelve thousand thousand years ago, when the dunes were rivers and the heat was gentle—more fun day at the spa than a metaphysical crisis.

In his The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, T.E. Lawrence makes you feel the heat, the thirst, the fatigue—he doesn’t just tell you there’s a desert, he drags you into it, kicks you in the ribs, and makes you drink sand for breakfast.

Lawrence gives you sunstroke, dust in your soul, and existential vertigo. Coelho gives you a thumbs-up and says.. don’t sweat it, buddy (Of course — who’s gonna break a sweat here? It’s not like we’re in the desert, are we?) Coelho writes for people who think they’ve found themselves after buying a scented candle and an Enya CD in a discount bin. Every line sounds like it’s been embroidered on a throw pillow by your auntie

who “does yoga now.”

The old masters wrote with blood. Today’s darlings write with essential oils and oat milk.

I ask, where is the filth of Bukowski, the chaos of Burroughs, the wanderlust of Kerouac? Where is the divine that made Beckett shrug and say, “I can’t go on, I’ll go on”? Modern writers go on, yes, yes—but I wish they’d stop. KEROUACIAN KRAKEN KATASTROPHE, please stop.

Of course, there are still modern writers that write with teeth and spit. Michel Houellebecq, Karl Ove Knausgård, Sjón, Hanya Yanagihara, countless others — they still write with dirt under their fingernails. Still refuse to be nice. They have prose that punches you in the face, wipes its hands on your conscience, offers a handkerchief, maybe a polite apology in a foreign language, then laughs as it drags your soul through the gutter. Beautiful, grotesque, irresistible.

But unfortunately, you won’t find their faces displayed at bookstores like movie stars.

Nope, you’ll only find sick, hopeless, terminal cases.

Monitors flatline.

Call it, doc.

Print is dead.

CHAPTER II

Post Tenebras Lux

After Darkness, Light

And so, imagine my astonishment when, in this barren wasteland of words, I stumbled upon a book that shook me to the core. A work of staggering simplicity. A text so honest, it bypassed the intellect and went straight for the soul—like accidentally downing a bottle of drain cleaner.

Its sentences cut clean through centuries of literary pretense. Almost Hemingway-like, if Hemingway had written The Old Man and the Sea with crayons.

I sat there, staring at the damn drawings—yeah, it had drawings, so what? I like drawings in my books, alright? Words alone get too cocky sometimes.

And then it hit me—like someone kicked the door of my skull wide open.

The author, Tom Karen, had done what no writer had dared in decades. He had written about something real. Something universal. Something no philosopher, no poet, no modern messiah had ever dared to confront with such clarity and courage.

He had written—about bottoms.

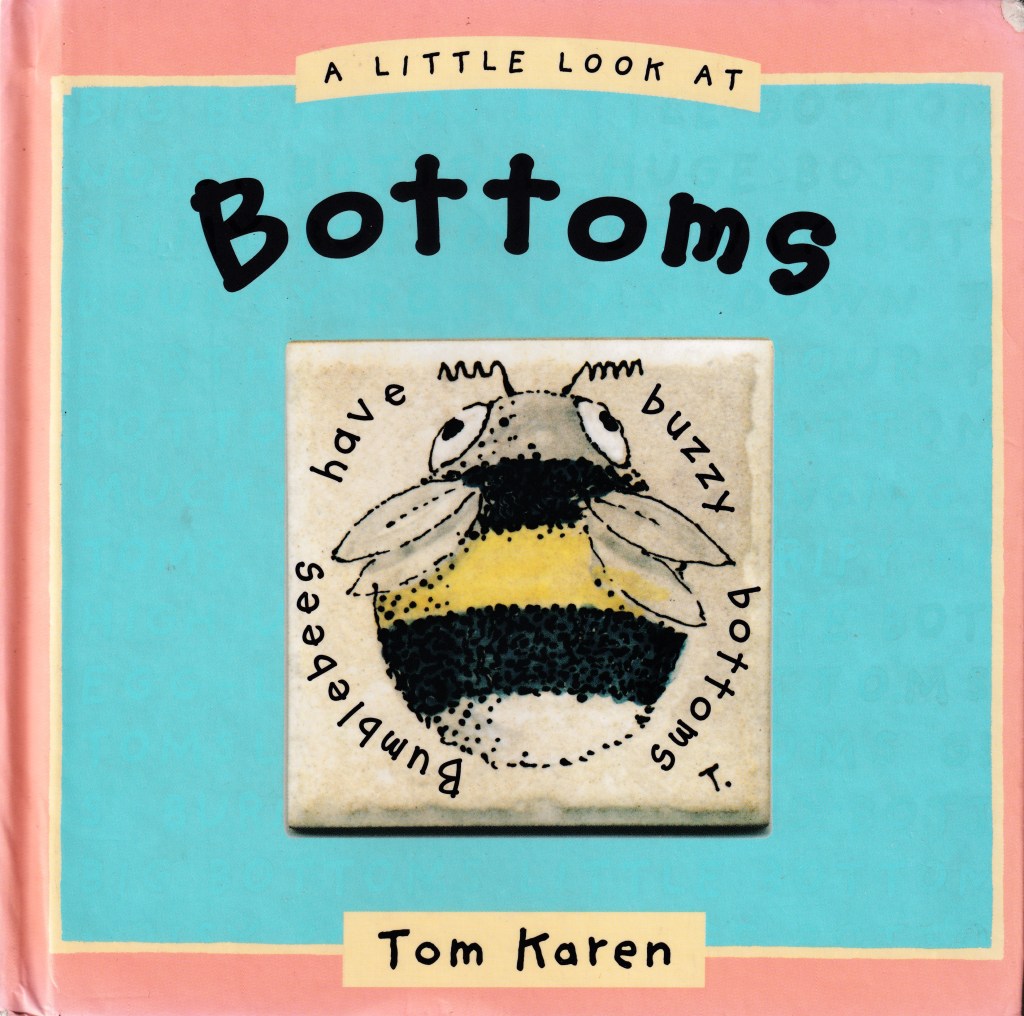

Yes. A Little Look at Bottoms.

And I, a grown man with a bookshelf full of Tolstoys, Heideggers, and Schopenhauers, found myself contemplating the divine curvature of an elephant.

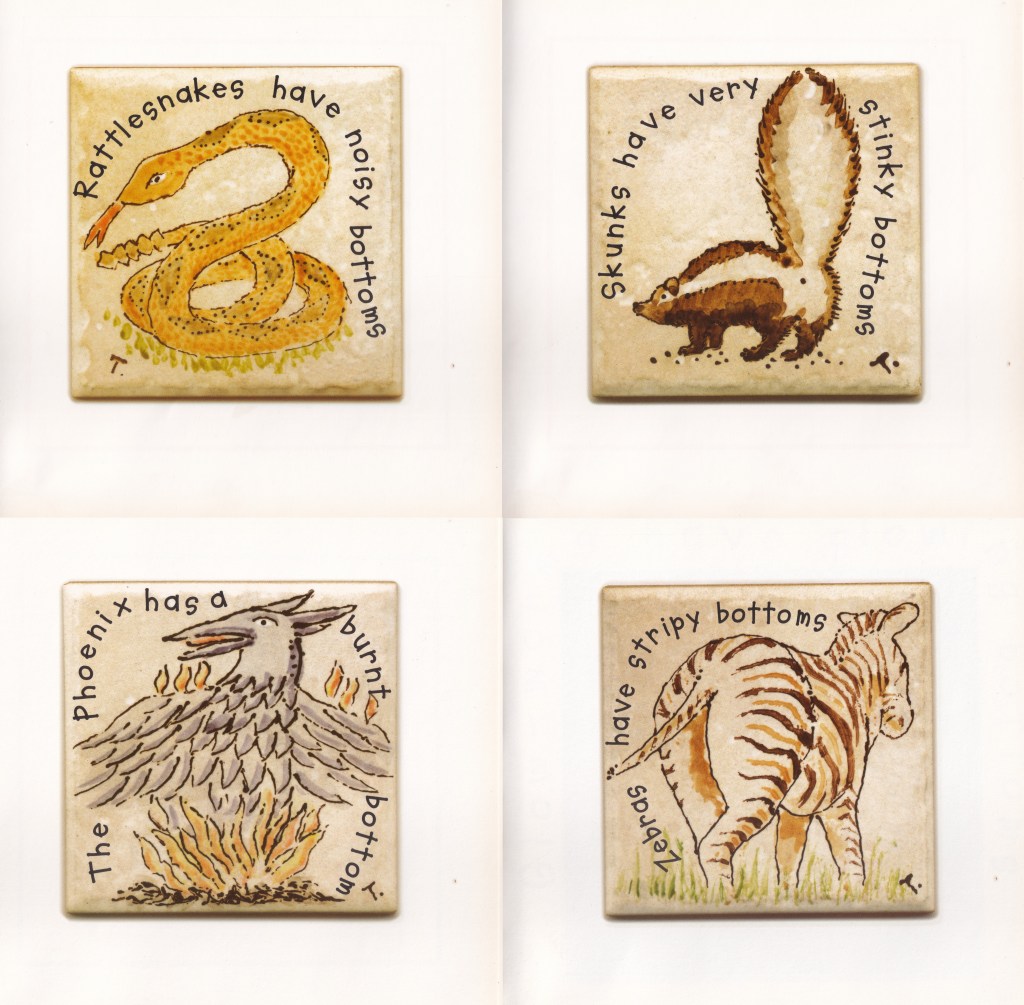

Each page was an awakening. A revelation. The giraffe, the walrus, the armadillo—all presented with egalitarian reverence. This was no mere children’s book. This was a treatise on existence.

In this world of ours, there are very few things we can call solid facts. Death is one. Death is the final encore, the last cigarette before lights out. Everything dies—the sun, the moon, your favorite band, your youth.

And the other great certainty: every living being, from the humblest amoeba to the proudest peacock—has a bottom.

That’s it. That’s the gospel. The eternal symmetry of existence. The great cosmic equalizer.

Think about it—emperors and earthworms, prophets and politicians, angels and accountants—all united by the humble rear.

You can talk about class struggle, theology, political upheaval, AI, the human condition—all of it—but nothing binds us together like the universal rear. Empires have fallen, revolutions have risen, prophets have preached—but not one among them could deny the simple, rounded truth sitting behind them.

History itself, when you peel away the grand speeches and epic battles, is just a story of powerful men covering their asses while exposing everyone else’s.

Tom Karen, in his infinite wisdom, has drawn not just animals—but mirrors. Mirrors of humility. Mirrors that remind us that even the noblest among us must, from time to time, sit down.

Children will laugh, of course. That is their shortcoming. But adults—if they have not been completely destroyed by cynicism—will see the Tao in those pages.

And so, I close this book with gratitude. Because in an age where writers strive to be profound by being incomprehensible, Tom Karen gives us the most honest philosophy of all.

If indeed, everything has a bottom—

then no wonder, my friend,

life stinks.

Leave a comment